Even in a chock-a-block 20th century calendar, the year 1980 seems particularly busy and significant. It marked the fall of disco and the early stirrings of New Wave, the assassination of John Lennon and the launch of the Rubix Cube. In 1980, Saddam Hussein invaded Iran, Reagan beat the political snot out of Jimmy Carter, and the world got its first 24-hour news channel, CNN. That year, the World Health Organisation announced arguably the single greatest humanitarian achievement of the century – the eradication of smallpox.

And on December 11, 1980, in the living room of his home in Milan, painter, designer and moustachioed ex-soldier Ettore Sottsass gathered a bunch of colleagues to discuss (what he saw as) the problem with ‘modern’ design.

In the room were some of the most talented creatives in Europe: radical French architect Martine Bedin, visionary Italian designer Aldo Cibic, award-winning industrial designer Michele De Lucchi – who these days spends his seventies carving wooden houses, armed with nothing but a chainsaw – plus Nathalie Du Pasquier, Matteo Thun and George J. Sowden. It was one of those rooms, and those moments, in which you would have paid good liras to be a fly on the wall.

While the designers tossed ideas around, and the sun sank behind the Alps, Bob Dylan’s 1966 track Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again played over and over in the background.

This little gathering marked the spiritual beginning of one of the most controversial artistic collectives of the last 50 years: Memphis Milano, also known as the Memphis Group.

There’s always been some debate over the origins of the name. Some say ‘Memphis’ was lifted from the Dylan track, stuck on a loop during that first meeting. Others say it was chosen because it’s the city where Elvis Presley lived (not to be confused with the capital of Ancient Egypt). Whatever the case, pretty soon some other big names had joined the fray, including Andrea Branzi, Shiro Kuramata, Marco Zanini, Peter Shire, Gerard Taylor, Masanori Umeda, Arquitectonica, Michael Graves, Hans Hollein, Arata Isozaki and Javier Mariscal.

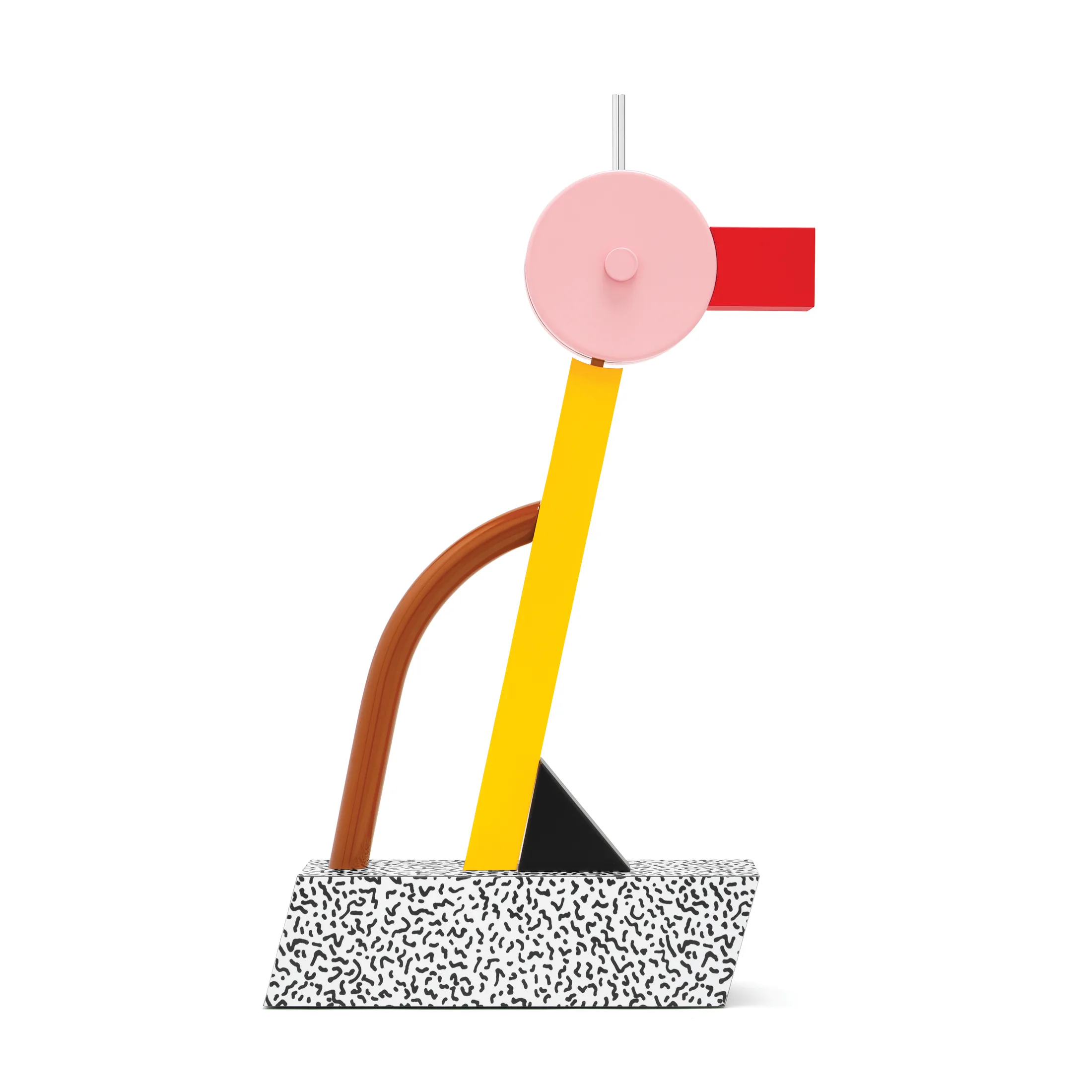

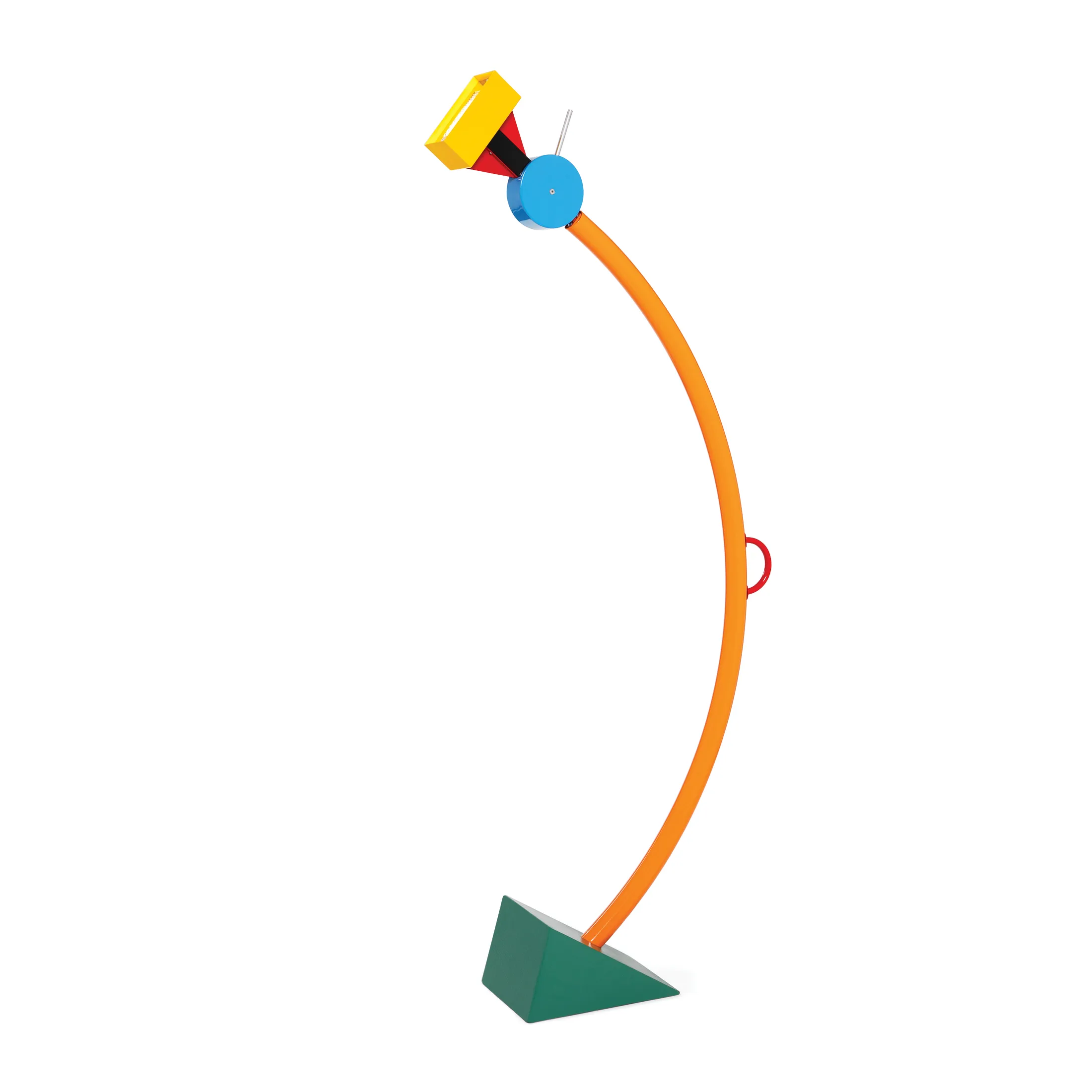

About nine months later, on 19 September 1981, at the gallery Arc '74, during Milan’s Salone del Mobile, Memphis came out to the world. It was their first exhibition: 55 pieces of furniture and industrial design that smashed everyone’s pre-conceived notions of good design, or even good taste. A few months after that, over 400 journals were practically buzzing with Memphis articles, dissections, critiques and martini-fuelled diatribes.

Modernism was officially dead in the water. Postmodernism, whatever that was, had arrived.

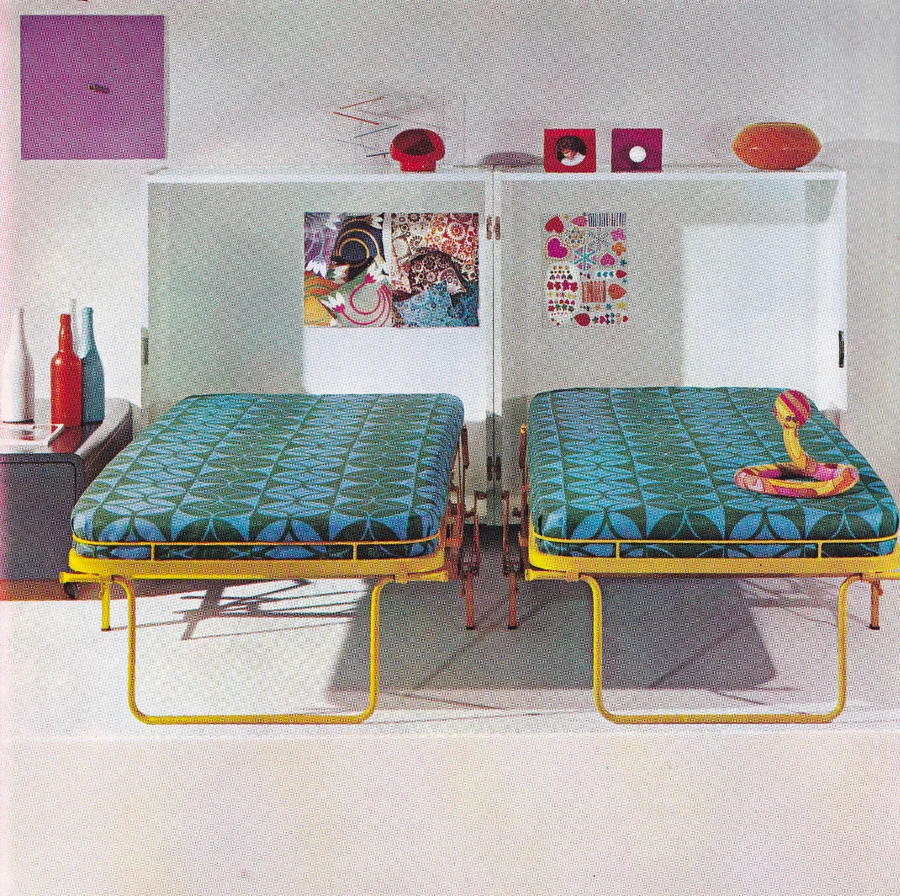

Throw a blanket over some of the most recognisable style cues of the 1980s – loud, obnoxious colour blocking, Pop Art, the liberal use of hot pink and electric blue, a weird fascination with techno-futurism, abstract geometric forms, maximalism in all things, especially perms – and you can trace them all back to Memphis Milano. Well, except the hair thing. The collective was a very deliberate attack on the form-follows-function austerity of mid-century modernism, where a thing’s inherent goodness correlated directly to stuff like ease-of-use, convenience and straight-lined simplicity. Yawn.

"When I was young, all we ever heard about was functionalism, functionalism, functionalism,”