Compared to other European capitals, or even Barcelona, Madrid is a uniquely forgettable city. It looks a bit like Paris, but with all the landmarks taken out: wide boulevards, tall buildings, no orientation points. It is the second-biggest city in the EU, its fourth largest urban economy – but if we played charades, or Pictionary, what would you draw if you had to draw me Madrid?

Some of it is due to history. In 1561, King Philip II got tired of touring his disjointed Spanish possessions on horseback – itinerant courts were by then seen as an outdated, medieval practice. Philip fancied himself a modern leader, with an interest in modern urbanism, which in late Renaissance meant public plazas, a grid of wide streets, geometry, symmetry. So he chose a provincial town, smack-bang in the geographical centre of Spain, and built there an administrative centre of his empire. Madrid, in other words, was the Canberra of its time.

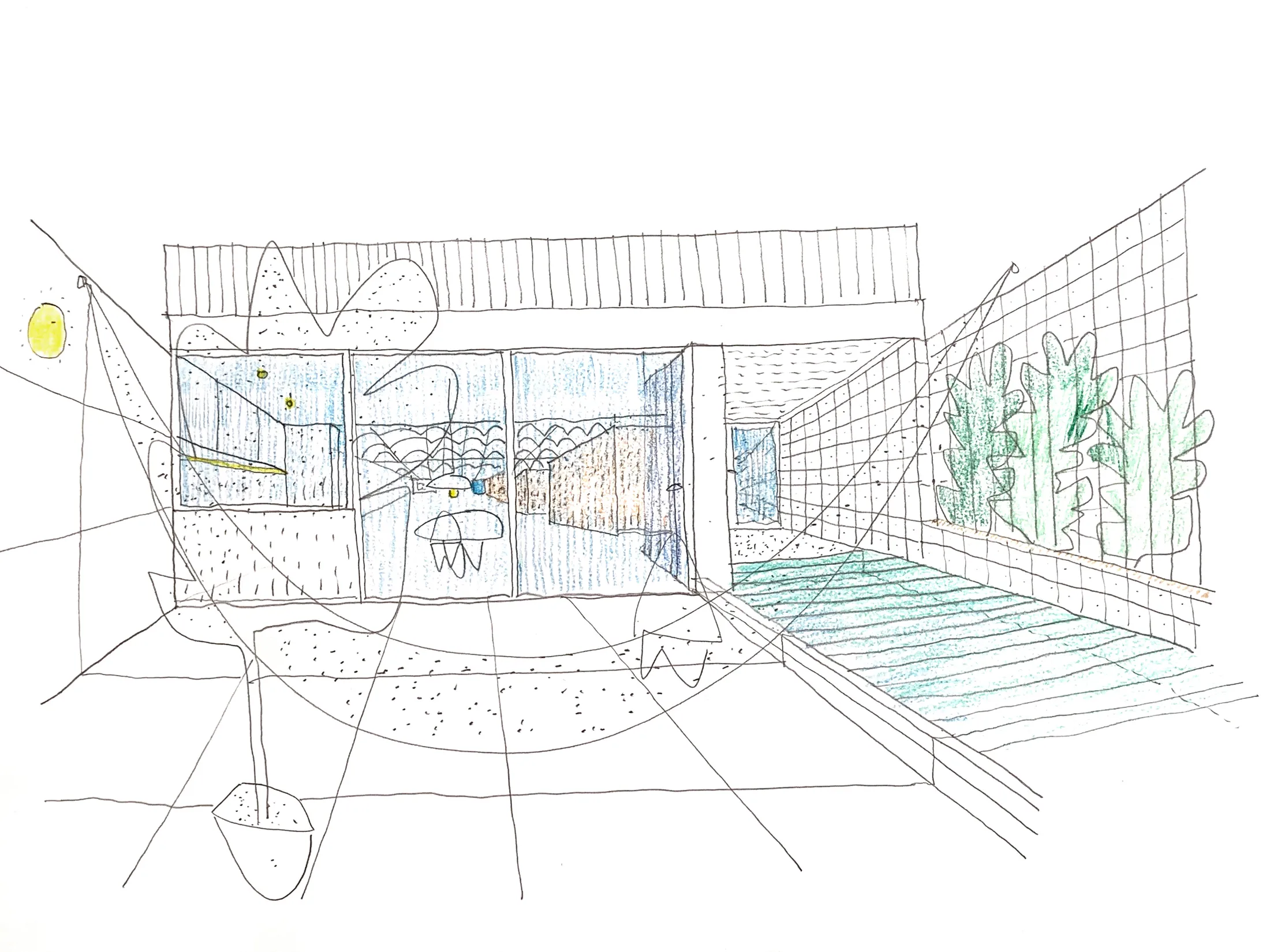

I feel this acutely while I’m circling a nondescript building in a nondescript neighbourhood, looking for gon architects’ office. There seems to be no care given to the public spaces, nor to the image they project. gon is a busy office, currently working across Spain, and increasingly Europe, on some 20 projects, ranging from cabinet handles to apartment buildings. I am expecting a flashy office in a hip neighbourhood. Instead, I am in a residential street with a primary school at one end. The only commercial signage is for a ground-floor photocopy shop. María Camila Martinez (also known as Maclas), gon’s communications coordinator, has to come down to find me.

“It’s true, we don’t have big monuments,” Gonzalo tells me. “Madrid isn’t special in that way. But it’s very special in other ways. You will see.”

“Madrid is a mess,” agrees Carol Pierina Linares, who has been something of Gonzalo’s right hand for the past 6-7 years. “In Barcelona, the city hires people who make sure that the level of public architecture is very fine. In Madrid, we’re missing public policies that really care about architecture.”

The contrast between the bland city outside, and the inventive, forward-thinking realm I have just entered, couldn’t be starker. gon’s team has largely come through the interdisciplinary, open-minded Master of Architectural Communication at Madrid’s polytechnic (MACA), where Gonzalo, then Carol, have taught. Their thinking is broad, with references ranging from Georges Perec’s wordplay novels and the mid-century projects of Ray and Charles Eames, to sociological studies. (“I think all of us could be in another profession if we wanted to,” Carol muses.) And there is a whimsy and playfulness that infuses their universe. Casa Flix was inspired by Wes Anderson movies. They have made an apartment entirely decked out in a particular shade of mint green used by Prada (Menta, 2021). They have turned a shopfront into a pull-out Latin American street food cart in a bright lime colour (Limeñita, 2022). And in their office, a large model of their latest apartment building is being attacked by a dinosaur figurine.

It’s a young and international office: apart from Carol and María (Maclas), there is María (Coti) and Maria (the Greek), all sitting around one big desk. Carol and Coti are Venezuelan, Maclas from Colombia. The atmosphere is warm and relaxed. The company Slack is a constant stream of memes. Banter and laughter fill the air, punctured by a loud hourly chirp.

“This is our bird clock!” says Gonzalo. “It’s a different bird sound every hour, and you have to guess the bird.” It’s their office game, he adds. Carol pipes in: “There is one bird that sounds like a pig!”

--

Gonzalo graduated in 2008, straight into the global financial crisis, which hit Spain particularly hard. The construction sector collapsed, leaving some 4 million vacant homes and a youth unemployment rate of 55 per cent. “The generation before us graduated and expected to immediately build buildings,” he says. “We all had to look for other types of work.” He was among the lucky ones, winning a major public competition straight out of university. Still, he was part of a generation that branched out into research, teaching and curation – and in the process, developed a more politically and environmentally aware approach to architecture.

We are eating lunch at Run Run Run, a restaurant with its own greenhouse, showers and lockers for the local running club, a building-manifesto to local food production, community and sustainability. It was designed by Andres Jaque, another prominent representative of the ‘crisis generation’. Looking outside from its mayhem of colours, textures, plants and customers, the drab street is another universe. The generational gap is palpable.

Maclas is organising me a ticket for an awards gala that evening. gon has been nominated for Casavera (2024), a shopfront in Valencia refurbished into an accessible family home for Elies, wheelchair-bound entrepreneur and activist, his artist wife Aurora, and their daughter Vera.

“In housing competitions, Madrid still talks about apartments ‘for a married couple’,” Carol tells me, visibly miffed. “Come on! Not only married people need housing!” They have completed accessible homes, homes for a single mum, for a single woman, for co-living, she says. “There are different ways of living. We try to enable them through architecture – that’s where we find the richness of life.”

Gonzalo tells me they start every project by interviewing the client in depth about how they live: how they cook, how they have sex, whether they prefer a bath or a shower…

“Sorry, wait,” I interrupt. “You ask them how they have sex?”

“Well, yes,” Gonzalo nods. “It’s really important! And they go: ‘Oh, uh, do we have to answer?’ Yes, you have to answer.” There is something genuine and charming in Gonzalo’s explanation, and by now we’re all roaring with laughter. “But,” he continues, “it’s really interesting what we discover. Many of them have been living their lives as their father and mother have told them. They discover, for example, that, if they cook a lot, they can have a big kitchen in the middle of the house. ‘Can I really have this?’ Of course you can!