When Malaysian landscape architect and urban designer Ng Sek San visits a destination, the first thing he does is seek out the slums. The poorest of the poor neighbourhoods. Places so removed from our traditional notions of architectural ‘style’ and ‘beauty’ as to make those concepts seem almost obscene. Like haute cuisine in the middle of a famine.

“That’s where I get a lot of my inspiration,” Sek San admits. “I walk in slums. I photograph slums. I look at scale and light, and how they use local materials, including cardboard. Because all those things are free of charge. Scale is free of charge. Light is free of charge.

“When people have no resources, but they have dignity, that’s when creativity gets maxed.”

It’s not the typical holiday beat you’d expect from a world-renowned architect. But then Sek San Ng isn’t really your standard commercial operator. Over a much-chronicled 40-year career, this rebellious, do-more-with-less spirit has given him some very firm ideas about how buildings should actually be built.

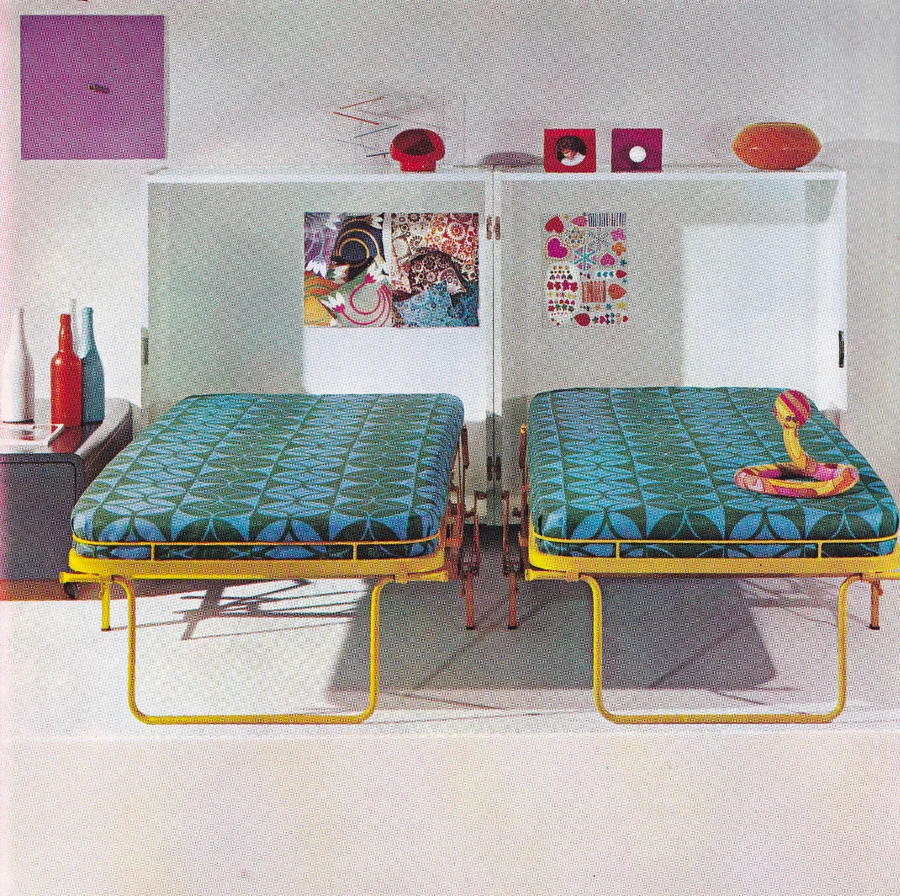

For one thing, they should be cheap. Not in the sense of poor quality or cutting corners for the sake of profit, but literally affordable to build. And to live in. Designed to maximise the wellbeing of the maximum number of people.

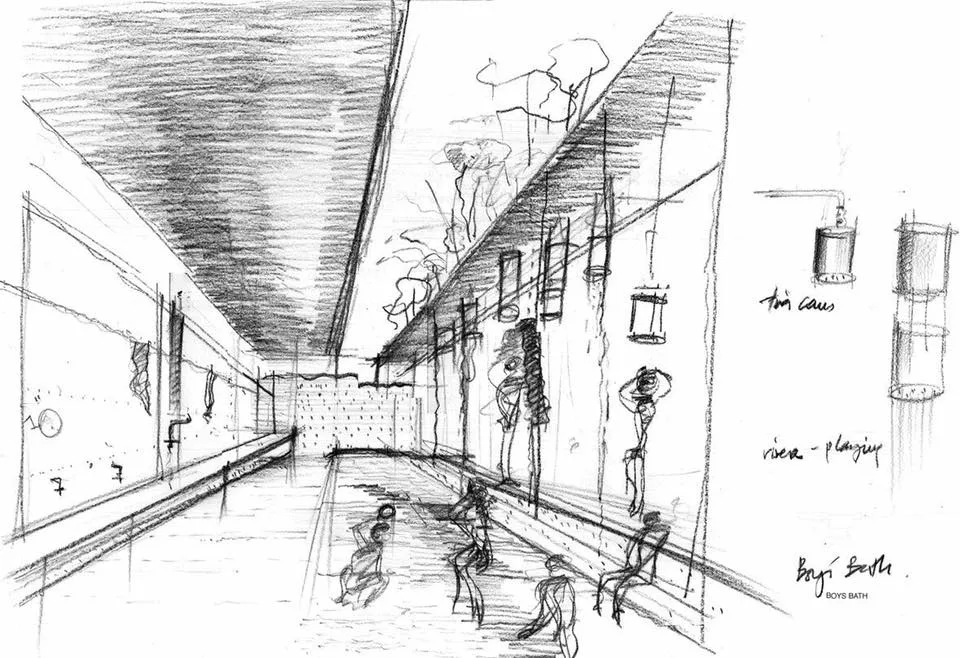

While most commercial developers might allocate 70 per cent of their budget to materials and 30 per cent to labour, for example, Sek San reverses that ratio. He employs local builders wherever possible, pays them good wages, and builds his buildings from deliberately unglamorous, home-spun materials: concrete, recycled timber, old copper pipes, forgotten industrial machinery, recycled signage, cardboard. Anything he can get his hands on. Imperfections aren’t just tolerated, they’re celebrated. Nothing is wasted, and nothing travels a single mile more than necessary.

This not only keeps costs low, but allows Sek San to limit the carbon footprint of his projects.

Double-glazed windows? Meh. A frivolous luxury. In Malaysia, where humidity tops 80 per cent and summer temperatures regularly hit 30 degrees celsius, glass is considered a premium material, usually reserved for big-budget commercial jobs and climate-controlled residential compounds. As such, many of Sek San’s buildings have no closeable windows and very few doors. Light, air and people are encouraged to flow through a space uninhibited. Birds literally nest in his office in downtown Kuala Lumpur.

Integrated heating and cooling? Nope. Instead, Sek San opts for plants, which ramble and creep over his designs in dense green curtains, providing low-cost insulation, passive cooling and free oxygen – all at the same time. Trees sprout not just through the floor, but through furniture. Roofs are often clear plastic, because that’s the cheapest way to keep the rain out and let light in. After a couple of years, Sek San’s jungle projects tend to look less ‘built’ and more extruded from the landscape, like overgrown temples from some ancient civilisation with impeccable taste.

“I don’t need cladding or windows,” Sek San says, “just time for the plants to grow. I’ve always said that time should finish a project for us. It’s the fourth dimension of a building. You know, modern buildings, they look good at the beginning, but then they start to deteriorate. I think a good building should be timeless.”