We all know Athens, or rather think we know it: Acropolis, Parthenon, ancient ruins, maybe a cypress in between. So it’s fair to say I'm startled when the airport taxi takes me on a giant freeway, into a city that looks, of all the places I know, mostly like Bangkok. The concrete is relentless: underpasses, overpasses, flat roofs, apartment buildings at every angle to one another. A sea of grey, in every direction, to the horizon.

“Excuse me, how big is Athens?” I ask the taxi driver.

“Five million,” he says, as if it were nothing.

“And how many people live in Greece?” I ask, uncertainly.

“Eleven million,” he nods. I gasp. Half of the country is crammed into this concrete monster-city we're heading into, clearly not the quiet seaside town of my expectations.

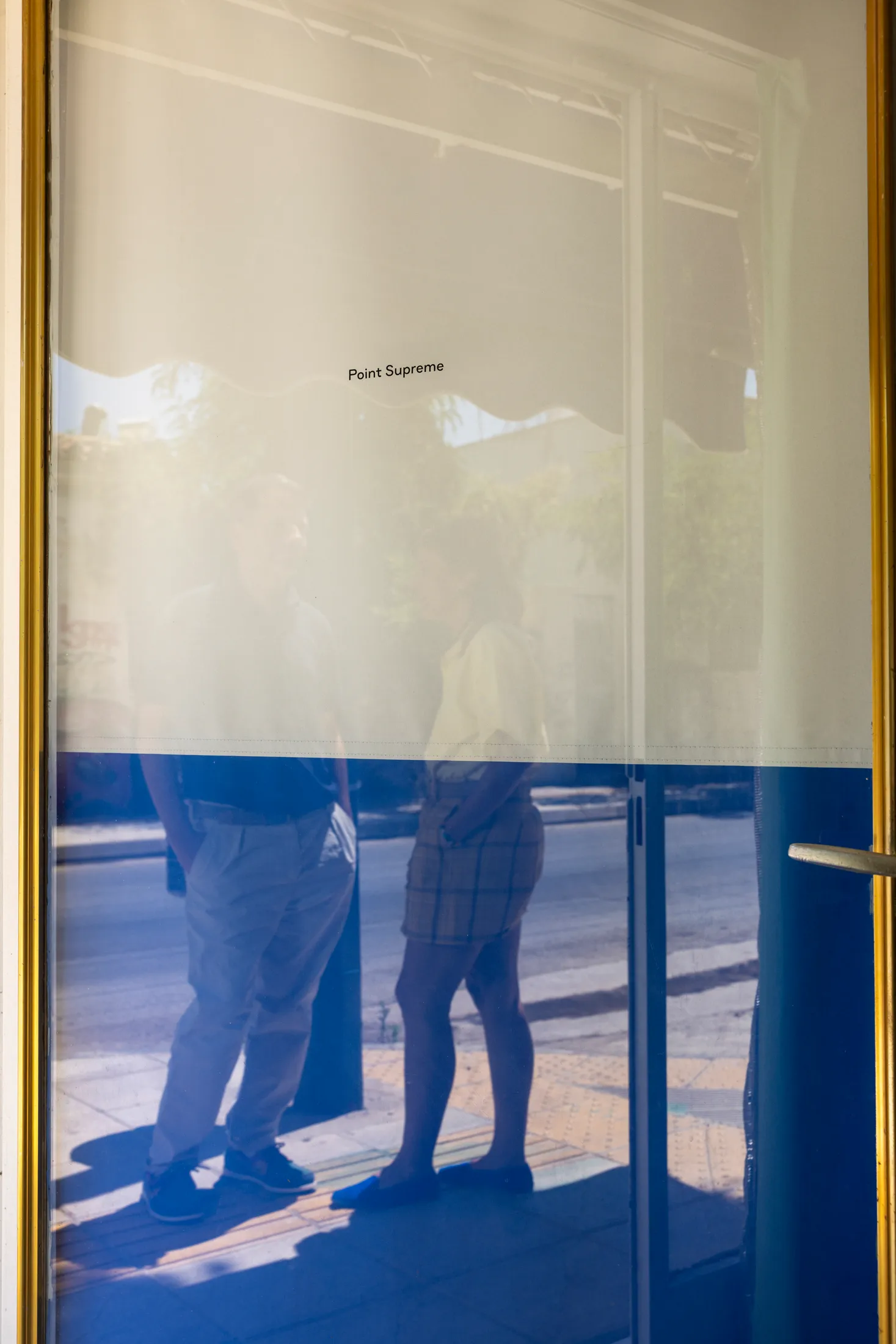

These expectations, I soon find out, are exactly what animates the work of Marianna Rentzou and Konstantinos Pantazis: architects, researchers and university professors, better known as Point Supreme.

In 2017, at Columbia University in New York, Point Supreme opened their lecture with a collage of postcards of Athens. Acropolis, Parthenon, vases, sculptures, an illuminated cypress hill. You would be forgiven for thinking there isn't a single modern building in all of Greece.

“You don't see the city at all in popular communication,” Pantazis said to the American students. “Never what Athens really is, this thing in-between ancient remains.” They zoom out to show “a formless lava” of a megalopolis shaped only by the topography – hills on three sides of the city, the sea on the fourth. “Every typical neighbourhood of Athens is continuous urbanisation made up of the same module, always.” The module: a five or six-storey apartment building, with top floors set back to let the sun reach the street. This type of building is called a polykatoikia, literally 'multiresidence'. “This is what Athens is actually made of.”

Ancient Athens, the city of our history books, largely declined with the rise of Christianity in the early centuries CE, and was later subsumed into the Ottoman Empire (modern Turkey). By the time Greece became independent again, in 1821, Athens was a village of 400 houses scattered around the Acropolis hill, and was made capital largely for sentimental reasons. Only after WWII did the city rapidly grow, on the influx of refugees. All polykatoikies were originally single-family houses. “There was no money, so an interesting bottom-up process was devised. The owners of little plots would give land to the builder, and in exchange for building an apartment building, they would give some apartments, or whole floors, to the owner,” Pantazis tells me. “It bypassed the need for cash, but it also bypassed any masterplanning procedure or large-scale developments, so there are none in Athens.” Built haphazardly, usually without an architect, to a simple template, polykatoikies were universally scorned by architects and Athenians alike. Nobody considered them beautiful or remarkable. That is, until Point Supreme moved into town.

“We take reality very seriously,” Pantazis told Columbia students in 2017. “The point [of our work] is not to propose new cities, but to take the existing reality and try to see it differently.”

--

Konstatinos Pantazis grew up in the small coastal city of Patras. “I didn't have a clue what architecture was. I wanted to be a painter. My mother was a painter, and my father had a fabric shop. I grew up looking at fabrics and colours.” He entered architecture school for a girl. Rentzou’s story is even more unlikely: a brilliant student from a small village, she studied computer science and chemical engineering before switching to architecture. The two started dating at uni – they've now been a couple for almost 30 years.

“Most of our classmates were sons of architects. They all grew up knowing Mies van der Rohe, copying the same designs.” Not being from Athens, not having family connections in the architectural world, Pantazis said, probably worked in their favour. They approached Athens, and architectural dogmas, with a free spirit.

They are critical of the education they received. It was a lot of Modernism, they say: strict rules on how things should look, how they should be built. Scorn heaped at decoration. “I remember the first house I designed for university: a modern box, gigantic and concrete, with three dots of colour,” Pantazis shakes his head. What was missing is what Rentzou and Pantazis call ‘Greekness’: the ordinary, everyday aesthetic they grew up with. “In seven years of architecture school, colour was not mentioned to us even once.”

After graduation, they went straight abroad, hungrily looking for better ideas. “We had a really honest and deep fascination with foreign cultures,” says Pantazis. It was the time of the Super Dutch, a strong postmodern, conceptual movement spearheaded by Rem Koolhaas, who was writing books about the scary and joyous chaos of Coney Island, of Berlin behind the Wall, of places that grew without a plan (Koolhaas has since studied places like server farms and the industrialised countryside). “We were alarmed and curious.” But they were also interested in the humane, small-scale Scandinavian interiors, in Japan's ability to bind tradition and the future, in Brazilians’ houses that opened up to nature. “This kind of thinking kept opening doors and windows. We would discover, not one, but 20, 50 architects. It was all linked by our desire to bring different things together,” says Pantazis. “I think that instinctively, we felt there was no one architecture. We could never make a building that was modern, or postmodern, or minimal, or maximal. We were trying to understand what pieces worked for us, and why.”

They both studied and worked for a string of prestigious institutions, in Tokyo, Rotterdam, London, Brussels, never once working together. “Konstantinos had specific rules,” Rentzou laughs. “He said: we will get different experiences. I am going to Rotterdam, you are not coming with me. Because I was so much in love, I said OK.” Both ended up working with the Super Dutch protagonists, MVRDV and Rem Koolhaas’s OMA, which Rentzou in particular found very inspiring. She worked directly with Rem Koolhaas. Having always believed herself to be more mathematical than creative, at OMA she learnt to use rational problem-solving to create designs. “It helped me trust myself.“

That these two people from the Greek countryside – not a place known for cutting-edge architectural thinking – would rise to the top of global architectural practice, is remarkable. That they would then decide to return to Greece and build their practice there – in 2008, at the start of the financial crisis that devastated the Greek economy, politics, and society – is extraordinary. But most extraordinary of all is what they did upon return, gave Athens a hard, fresh look, and started reimagining it from scratch. Their work would transform how the city, perhaps even the country, saw itself.

--

“Until very recently, we thought we were very unlucky to have started the office in the crisis. We didn't have connections, or much work in the early years. So we started to do self-initiated projects – projects for the city nobody was asking for.”

Rentzou and Pantazis were struck by the gap between actual Athens and its tourist image. Real Athens seemed invisible even to its inhabitants. But they liked this real Athens, appreciated its wide blue skies, the mountains framing the city, the long vistas from rooftop terraces and deep balconies where ordinary life took place most of the year. They produced their own line of tourist memorabilia that celebrated ordinary Athenian neighbourhoods: tea towels, mugs, T-shirts. They produced a souvenir miniature replica of a polykatoikia in fine marble. They wrote to LEGO with a proposal to create a polykatoikia set (they never heard back). Referencing Hokusai’s 100 Views of Mount Fuji, they commissioned 100 Views of Acropolis: photographic vistas of the Parthenon as seen from rooftop loungers, suburban tennis courts, balconies, parking lots.